What Are Software-Defined Vehicles

Software-Defined Vehicles are road vehicles in which core functionality, features, and operational characteristics are primarily determined and controlled by software rather than fixed hardware configurations. They refer to automotive platforms where computing infrastructure, electronic control, and service delivery are abstracted from physical components, enabling continuous capability evolution through software updates, centralized processing architectures, and dynamic feature deployment throughout the vehicle lifecycle. In enterprise and public-sector contexts, they are used to enable subscription-based service models, reduce development cycle times, support regulatory compliance through remote updates, and establish data-driven operational intelligence across vehicle fleets and transportation systems.

Core Characteristics and Principles

Software-Defined Vehicles represent a fundamental architectural transition from distributed, hardware-specific vehicle control systems toward centralized or zonal computing platforms where software orchestrates vehicle behavior independent of underlying mechanical systems. This transformation parallels shifts observed in telecommunications infrastructure and data center operations, where software abstraction layers enable operational flexibility and continuous improvement without hardware replacement.

- Hardware Abstraction and Separation: Vehicle functions are decoupled from specific electronic control units through middleware and hardware abstraction layers, allowing software to execute across different processor architectures and enabling platform reuse across vehicle models and generations

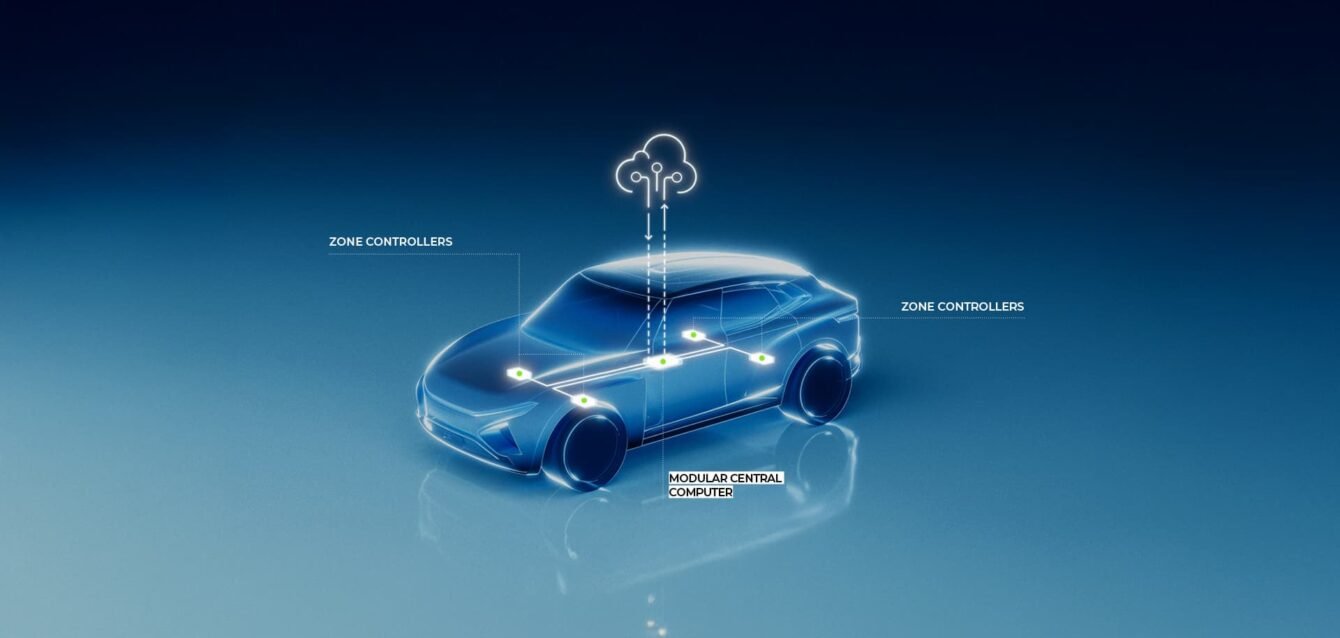

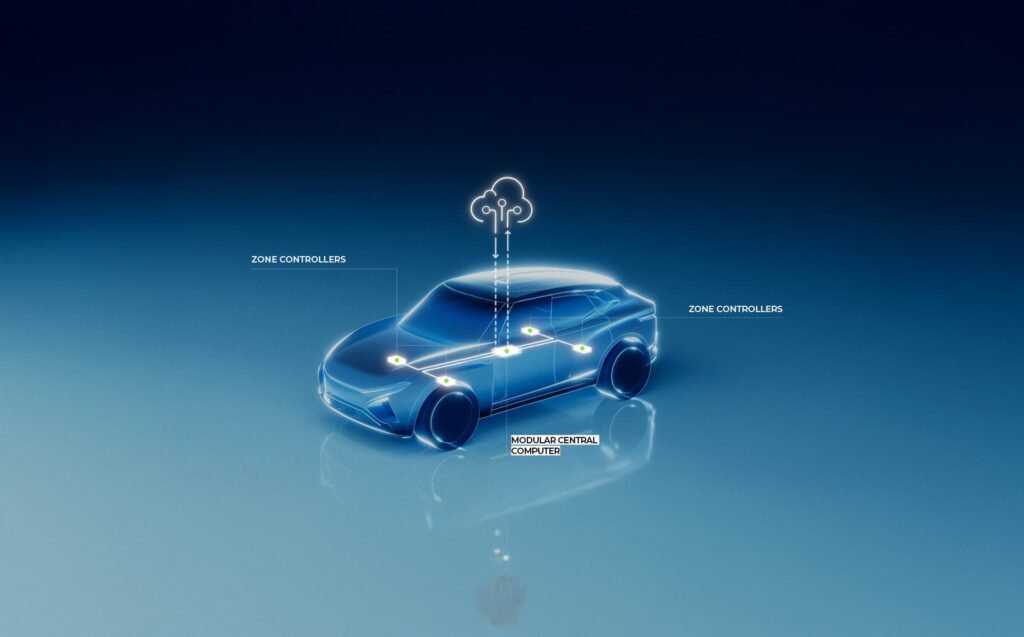

- Centralized or Zonal Computing Architecture: Processing transitions from distributed domain controllers toward fewer, more powerful compute platforms that manage multiple vehicle functions simultaneously, reducing wiring complexity, component count, and enabling software-based resource allocation

- Service-Oriented Architecture: Vehicle functions are implemented as discrete software services that communicate through standardized interfaces, enabling modular development, independent service deployment, and runtime reconfiguration of vehicle capabilities based on operational context or user preferences

- Over-the-Air Update Capability: Systematic mechanisms enable remote software deployment, security patching, and feature activation after production, requiring secure update channels, rollback provisions, and verification frameworks to maintain vehicle integrity and safety compliance

- Continuous Integration and Deployment: Development processes adopt iterative software engineering methodologies with automated testing, simulation-based validation, and staged deployment strategies that compress development cycles from years to months while maintaining safety requirements

- Data-Driven Operations and Intelligence: Vehicles generate, process, and transmit operational data to support predictive maintenance, usage-based services, fleet optimization, and continuous learning systems that improve performance through accumulated operational experience

- Ecosystem Integration and Standardization: According to NIST automotive research programs, software-defined platforms require standardized communication protocols, cybersecurity frameworks, and interoperability specifications to enable third-party service integration and cross-manufacturer compatibility

How It Works (Conceptual, Not Technical)

Software-Defined Vehicles operate through layered software architectures that progressively abstract vehicle functions from physical hardware, creating programmable platforms where capabilities are defined by code rather than mechanical design.

- Electrical-Electronic Architecture Transformation: Traditional vehicles employ distributed architectures with 70-100 independent electronic control units, each dedicated to specific functions. Software-Defined Vehicles consolidate this complexity into centralized high-performance computers or zonal controllers that execute multiple functions on shared hardware. This consolidation requires redesigned wiring harnesses, standardized communication protocols, and sophisticated software that manages resource allocation across competing demands.

- Software Stack Implementation: The vehicle software stack comprises multiple layers analogous to operating systems in computing environments. The lowest layers interface directly with hardware sensors, actuators, and power management. Middleware layers provide abstraction services, real-time operating systems, and communication infrastructure. Application layers implement user-facing features, advanced driver assistance functions, and connectivity services. This layered approach enables independent development and update of different stack components without requiring complete system redesign.

- Development Process Restructuring: Creating Software-Defined Vehicles requires organizational transformation from traditional automotive engineering toward software-centric development methodologies. Teams adopt continuous integration practices, simulation-based testing, and agile development cycles. Validation occurs through virtual environments, hardware-in-the-loop testing, and staged real-world deployment. Development organizations establish software platforms that serve as foundations for multiple vehicle programs, enabling code reuse and accelerating time-to-market.

- Feature Deployment and Lifecycle Management: Once vehicles enter service, capabilities evolve through software updates rather than remaining static. Organizations establish secure update delivery mechanisms, testing protocols for deployed software, and rollback procedures for problematic updates. Feature activation can occur based on subscription status, regulatory approval, or operational context. This ongoing relationship between manufacturer and vehicle requires sustained infrastructure investment and customer relationship management capabilities.

- Data Flow and Processing Architecture: Software-Defined Vehicles continuously generate sensor data, operational telemetry, and user interaction information. Processing occurs both within the vehicle through edge computing capabilities and in cloud infrastructure where aggregated fleet data enables machine learning model training, predictive analytics, and service optimization. Data governance frameworks address privacy requirements, security concerns, and regulatory compliance while enabling value extraction from vehicle-generated information.

- Safety and Reliability Assurance: Ensuring safety in software-defined systems requires systematic approaches to software validation, fail-safe mechanisms, and runtime monitoring. Organizations implement redundant processing, watchdog functions, and safe-state fallback behaviors. Software undergoes formal verification processes, security testing, and compliance validation against functional safety standards. Systematic evidence generation demonstrates that software-driven systems maintain equivalent or superior safety compared to traditional mechanically-linked controls.

Common Use Cases in Enterprise and Government

Fleet Operations and Commercial Transportation

Commercial fleet operators deploy Software-Defined Vehicles to enable centralized fleet management, remote diagnostics, and operational optimization across distributed vehicle populations. Software-defined platforms support dynamic route optimization, load management, and driver behavior monitoring. Fleet managers implement usage-based maintenance scheduling, energy consumption optimization for electric vehicles, and compliance monitoring for regulated operations. Remote update capability reduces vehicle downtime by deploying software improvements without requiring physical service interventions.

Automotive Manufacturing and Product Development

Original equipment manufacturers utilize software-defined architectures to reduce development costs and accelerate product introduction cycles. Platform strategies enable code sharing across vehicle segments, reducing redundant engineering effort. Software-defined approaches support rapid response to regulatory changes through remote updates rather than hardware recalls. Manufacturers establish software organizations with thousands of developers, partnering with technology companies to acquire capabilities in cloud infrastructure, artificial intelligence, and cybersecurity that traditional automotive engineering organizations lack.

Public Transportation and Municipal Mobility

Transit agencies deploy software-defined buses and rail vehicles that integrate with smart city infrastructure, enabling dynamic schedule optimization, passenger information systems, and contactless payment integration. Software updates support regulatory compliance for emissions monitoring, accessibility features, and safety system enhancements. Municipalities leverage vehicle-generated data for infrastructure planning, service optimization, and mobility-as-a-service program development. Software-defined platforms enable experimental deployments of autonomous shuttle services within controlled operational domains.

Defense and Government Vehicle Operations

Military and government agencies implement software-defined platforms in tactical vehicles, support equipment, and specialized transportation systems. Software abstraction enables rapid reconfiguration for changing mission requirements, integration with command and control systems, and cybersecurity hardening for contested operational environments. Government agencies establish validation frameworks for software-defined military vehicles that address adversarial conditions, electromagnetic warfare environments, and mission-critical reliability requirements not encountered in commercial applications.

Automotive Supplier and Component Manufacturing

Tier 1 and Tier 2 suppliers transition from delivering physical components toward providing software services, cloud infrastructure, and system integration expertise. Suppliers develop middleware platforms, implement machine learning algorithms for perception systems, and establish cybersecurity capabilities that protect supply chain integrity. According to research on software-defined vehicle adoption, suppliers face organizational transformation challenges as traditional mechanical engineering expertise becomes insufficient for software-centric product development.

Insurance and Risk Management Services

Insurance providers develop usage-based insurance products enabled by continuous vehicle data collection from software-defined platforms. Telematics integration supports dynamic premium calculation based on actual driving behavior, environmental conditions, and vehicle condition monitoring. Risk management organizations leverage fleet-wide data analysis to identify safety trends, predict incident likelihood, and develop targeted intervention strategies that reduce claim frequency and severity.

Strategic Value and Organizational Implications

Software-Defined Vehicles fundamentally alter competitive dynamics, value capture mechanisms, and organizational structures within automotive ecosystems. The transition represents not merely a technical evolution but a business model transformation comparable to shifts experienced in telecommunications, media distribution, and enterprise computing infrastructure.

From a strategic positioning perspective, software-defined architectures create opportunities for ongoing customer relationships through subscription services, feature-on-demand offerings, and data monetization that extend beyond traditional vehicle sales transactions. Organizations establishing successful software platforms can capture recurring revenue streams throughout vehicle lifecycles rather than realizing value solely at point of sale. Market analysis indicates the software-defined vehicle market may expand from $470 billion in 2026 to $1.19 trillion by 2036, representing growth rates substantially exceeding traditional automotive market expansion.

For enterprise decision-makers, software-defined approaches compress innovation cycles and reduce the capital intensity of product development. Platform architectures enable simultaneous development of multiple vehicle programs from shared codebases, reducing redundant engineering investment. Organizations can respond to competitive threats, regulatory changes, and market opportunities through software updates rather than requiring complete vehicle redesign and retooling of manufacturing facilities. This operational flexibility becomes increasingly valuable in volatile market conditions and during technological transitions.

Supply chain implications are profound. Traditional tier-based automotive supply structures organized around mechanical components face disruption as value creation shifts toward software capabilities, data services, and ecosystem integration. Suppliers with mature software engineering practices, cloud infrastructure expertise, and cybersecurity capabilities gain strategic advantage regardless of their historical position in mechanical supply chains. Conversely, suppliers lacking software competencies face commoditization pressure or exclusion from next-generation vehicle programs.

From an organizational capability perspective, software-defined vehicle development requires fundamentally different skill sets, development processes, and cultural attributes than traditional automotive engineering. Organizations must attract software talent from technology sectors, establish continuous deployment pipelines, and maintain operational infrastructure for over-the-air updates and cloud services. Many traditional automotive manufacturers partner with technology companies or acquire software organizations rather than developing all capabilities organically, creating complex joint venture structures and technology licensing arrangements.

Regulatory and liability frameworks struggle to accommodate software-defined vehicles where capabilities change post-production and responsibility for vehicle behavior involves manufacturers, software suppliers, infrastructure operators, and potentially the vehicles themselves in autonomous configurations. Organizations must navigate uncertain liability exposure, establish documentation practices for software verification, and coordinate with regulators developing frameworks for software-defined vehicle approval and ongoing compliance monitoring.

Risks, Limitations, and Structural Challenges

Cybersecurity and Safety Interdependence: Software-defined architectures concentrate critical vehicle functions in centralized computing platforms, creating single points of failure and attractive targets for cyber attacks. Compromised software can simultaneously affect entire vehicle fleets rather than isolated units. Organizations must implement defense-in-depth security architectures, intrusion detection systems, and incident response capabilities while maintaining real-time performance requirements. The complexity of securing software-defined vehicles exceeds traditional information technology security as attacks can directly threaten physical safety rather than merely compromising data confidentiality or availability.

Software Complexity and Verification Challenges: Modern software-defined vehicles contain 100-150 million lines of code, exceeding complexity of commercial aircraft and approaching scale of large enterprise software systems. Verifying correct operation across all possible states, environmental conditions, and failure modes becomes mathematically intractable. Organizations rely on simulation-based testing, formal verification of critical subsystems, and staged deployment strategies, but cannot achieve complete testing coverage. Latent software defects may manifest only after millions of vehicle operating hours, creating recall exposure and safety concerns.

Legacy Architecture and Technical Debt: Existing vehicle platforms were designed around distributed electronic control units with direct hardware interfaces and cannot be retroactively converted to software-defined architectures without complete redesign. Manufacturers face difficult decisions about maintaining legacy architectures for existing product lines while simultaneously developing new software-defined platforms. This dual-track approach consumes engineering resources, creates supply chain complexity, and delays realization of software-defined benefits. Organizations with extensive existing product portfolios face longer transition periods than new entrants designing software-defined architectures from inception.

Organizational and Cultural Transformation Requirements: Traditional automotive engineering organizations emphasize mechanical design expertise, extensive testing protocols, and conservative change management to ensure reliability in safety-critical applications. Software-defined development demands rapid iteration, continuous deployment, and comfort with incremental improvement rather than complete validation before release. Established manufacturers struggle to attract software talent competing with technology companies offering superior compensation, work environments, and career advancement opportunities. Cultural conflicts between traditional automotive engineering and software development methodologies impede organizational effectiveness.

Regulatory Uncertainty and Fragmentation: Existing vehicle regulations were developed for hardware-defined systems with fixed capabilities at time of type approval. Software-defined vehicles that gain new capabilities post-production challenge regulatory frameworks designed for static configurations. Different jurisdictions develop conflicting approaches to software-defined vehicle approval, over-the-air update authorization, and ongoing compliance verification. Organizations face regulatory complexity managing global vehicle populations where regional authorities impose different software requirements, creating demand for region-specific software variants and complicating global platform strategies.

Infrastructure and Ecosystem Dependencies: Software-defined vehicles depend on reliable cellular connectivity for over-the-air updates, cloud services for advanced features, and charging infrastructure for electric powertrains. Coverage gaps, network reliability issues, and infrastructure availability constraints affect feature availability and customer satisfaction. Organizations must coordinate with telecommunications providers, cloud infrastructure operators, and utility companies to ensure supporting infrastructure adequately serves vehicle requirements. Ecosystem dependencies create vulnerability to external service disruptions and complicate control over customer experience.

Skill Gap and Talent Competition: Developing software-defined vehicles requires expertise in cloud architecture, machine learning, cybersecurity, and embedded real-time systems that traditional automotive engineering programs do not emphasize. Organizations compete for talent with technology companies, defense contractors, and aerospace manufacturers, driving compensation escalation and talent retention challenges. Automotive manufacturers lack the institutional reputation in software development that major technology companies possess, hampering recruitment of experienced software architects and security specialists. Geographic concentration of software talent in technology hubs conflicts with automotive manufacturing locations, requiring distributed development models or major facility investments.

Relationship to Adjacent AI and Technology Concepts

Software-Defined Vehicles intersect substantially with artificial intelligence deployment in automotive applications, particularly for perception systems, decision-making algorithms, and personalization features. However, AI represents a capability deployed within software-defined architectures rather than defining the architecture itself. Machine learning models processing sensor data for autonomous driving, voice recognition for natural language interfaces, and predictive maintenance algorithms all execute on software-defined computing platforms. The relationship is hierarchical—software-defined architecture provides the computational infrastructure, communication mechanisms, and update pathways that enable AI algorithms to function and improve over vehicle lifetimes.

The connection to edge computing frameworks is fundamental. Software-defined vehicles represent mobile edge computing nodes that process substantial data volumes locally while coordinating with cloud infrastructure for model training, fleet-wide learning, and service delivery. Edge processing enables real-time responsiveness required for safety-critical functions while cloud connectivity supports continuous improvement through accumulated operational data. This hybrid architecture mirrors patterns in industrial Internet of Things deployments and telecommunications network virtualization.

Vehicle-to-everything communication systems depend on software-defined architectures for implementation. V2X capabilities require software that processes incoming messages, makes routing decisions, and coordinates with vehicle control systems. Software-defined platforms enable V2X algorithms to evolve as communication protocols mature, traffic management strategies develop, and infrastructure capabilities expand. The NIST automated vehicles program specifically addresses measurement science for V2X communications within software-defined vehicle contexts.

Relationship to platform business models from technology sectors is instructive. Software-defined vehicles enable platform strategies where manufacturers provide core infrastructure while third-party developers create applications and services. This approach mirrors smartphone ecosystems, cloud computing platforms, and industrial automation systems. However, safety criticality and regulatory requirements in automotive applications constrain openness compared to consumer technology platforms. Organizations must balance platform extensibility against safety assurance and maintain control over safety-critical functions while potentially enabling third-party innovation in non-safety-critical domains.

Digital twin technology provides virtual representations of physical vehicles used throughout development, testing, and operational phases. Software-defined architectures enable continuous synchronization between physical vehicles and their digital twins, supporting simulation-based testing of software updates before deployment, digital validation of proposed changes, and predictive analysis of component degradation. Digital twins become increasingly sophisticated as software-defined vehicles generate more detailed operational telemetry and enable more precise virtual modeling of vehicle behavior under varied conditions.

Why This Concept Matters in the Long Term

Software-Defined Vehicles represent the automotive industry’s response to technological convergence, changing consumer expectations, and competitive pressure from technology-native organizations entering mobility markets. The transition establishes automotive manufacturing as a software-intensive industry alongside aerospace, telecommunications, and defense sectors that experienced similar transformations in previous decades.

From a market structure perspective, software-defined approaches lower barriers to entry for new competitors while raising requirements for established manufacturers to maintain market position. Technology companies, electric vehicle startups, and mobility service providers can potentially achieve competitive feature sets more rapidly than traditional manufacturers burdened by legacy architectures and organizational structures. This dynamic accelerates industry consolidation, drives partnership formation, and potentially reshapes competitive hierarchies that remained stable for decades under hardware-centric competition.

The institutional significance extends to transportation infrastructure planning and smart city development. Software-defined vehicle fleets that communicate with infrastructure, share operational data, and enable coordinated mobility services become foundational elements of intelligent transportation systems. Municipal planners, transportation authorities, and infrastructure operators increasingly consider vehicle software capabilities when designing traffic management systems, establishing autonomous vehicle operating zones, and deploying mobility-as-a-service programs. The assumption that vehicles can receive software updates enabling new infrastructure interactions influences long-term infrastructure investment decisions.

For workforce development and educational institutions, software-defined vehicles necessitate curriculum reform in automotive engineering programs, establishment of interdisciplinary programs combining mechanical engineering with computer science, and continuing education programs for existing automotive workforce. Universities develop research programs addressing software-defined vehicle challenges in cybersecurity, functional safety, and artificial intelligence integration. Professional societies establish certification programs for software-defined vehicle development practices, creating professional development pathways for engineers transitioning from traditional automotive roles.

From a standardization perspective, software-defined vehicles drive development of new industry standards for software architectures, communication protocols, and lifecycle management processes. Standards development organizations like SAE International, ISO, and IEEE establish working groups addressing software-defined vehicle requirements. Industry consortia form to develop open-source platforms, establish reference architectures, and coordinate on common infrastructure requirements. This standardization activity influences technology choices throughout automotive supply chains and affects interoperability between vehicles from different manufacturers.

The environmental implications warrant consideration. Software-defined architectures enable more sophisticated energy management in electric vehicles, more accurate range prediction, and more effective battery degradation management through continuous software optimization. However, the computational requirements of software-defined vehicles increase power consumption, rare material usage in processors, and electronic waste generation as hardware platforms require more frequent replacement than traditional mechanical components. Organizations must balance software capability requirements against resource consumption and lifecycle environmental impact.

Enterprise Implementation Considerations

Development Organization and Skill Requirements

Establishing software-defined vehicle development capabilities requires organizational restructuring, talent acquisition, and process transformation that extends beyond traditional automotive engineering practices. Organizations must decide whether to develop software capabilities internally, partner with technology companies, acquire software organizations, or employ hybrid approaches combining internal development with external partnerships.

Internal development enables complete platform control, proprietary differentiation, and organizational learning but requires substantial investment, extended development timelines, and competitive recruitment in constrained talent markets. Technology partnerships accelerate capability development and provide access to proven platforms but create dependency relationships, potential intellectual property complications, and reduced differentiation. Acquisition strategies can rapidly establish software capabilities but involve integration challenges, cultural conflicts, and retention risks as acquired talent evaluates post-acquisition opportunities.

Development organizations require software architects who design system-level platforms, embedded systems engineers who implement real-time control software, cloud infrastructure specialists who deploy backend services, cybersecurity experts who implement defense mechanisms, and machine learning engineers who develop perception and decision algorithms. Traditional automotive organizations lack institutional experience recruiting, managing, and retaining these specialized roles. Compensation structures, career progression models, and work environments that succeed in automotive mechanical engineering often fail to attract and retain software talent accustomed to technology industry practices.

Agile development methodologies, continuous integration pipelines, and simulation-based validation represent standard practices in software development but conflict with traditional automotive stage-gate processes, extensive physical testing requirements, and conservative change management. Organizations must develop hybrid methodologies that maintain safety assurance and regulatory compliance while enabling iterative development and rapid deployment cycles. This methodological evolution requires training, tool investment, and cultural change throughout engineering organizations.

Platform Strategy and Architecture Decisions

Organizations face fundamental choices about software-defined vehicle platform strategies that affect development efficiency, feature differentiation, and competitive positioning for decades. Decisions about computing hardware architectures, operating system selection, middleware frameworks, and application programming interfaces establish constraints on future capability development and determine ecosystem participation opportunities.

Centralized computing architectures concentrate processing in few powerful computers that execute all vehicle functions. This approach maximizes hardware utilization, enables sophisticated resource allocation, and simplifies software architecture but creates single points of failure, concentrates heat generation, and complicates electromagnetic compatibility. Zonal architectures distribute processing across several zone controllers that manage vehicle regions, reducing wiring complexity while maintaining processing distribution. Hybrid approaches combine centralized and zonal elements to balance competing requirements.

Operating system selection involves tradeoffs between real-time determinism required for safety-critical functions and general-purpose capability needed for infotainment and connectivity features. Organizations choose between proprietary operating systems providing complete control but requiring substantial development investment, adapted real-time operating systems offering proven safety characteristics but limited application ecosystems, and Linux-based platforms providing extensive application support but requiring safety certification and real-time enhancement.

Middleware selection determines communication mechanisms, service discovery, and application integration approaches. Organizations adopt standards like AUTOSAR Adaptive for automotive-specific middleware, leverage general-purpose frameworks like ROS for robotics applications, or develop proprietary middleware optimized for their specific requirements. Middleware choices affect development productivity, ecosystem participation opportunities, and migration flexibility as architectures evolve.

Cybersecurity Architecture and Governance

Software-defined vehicles require comprehensive cybersecurity programs addressing threats throughout vehicle lifecycles from development through operation and decommissioning. Cybersecurity architecture implements defense-in-depth strategies combining cryptographic protections, network segmentation, intrusion detection, secure boot mechanisms, and runtime integrity monitoring. Organizations must balance security requirements against performance constraints, cost considerations, and functional requirements in resource-constrained embedded environments.

Cryptographic systems protect software integrity, authenticate communication, and establish trust relationships between vehicle systems and external entities. Hardware security modules store cryptographic keys, perform encryption operations, and provide tamper-resistant processing for security-critical functions. Public key infrastructure enables authentication of software updates, vehicle-to-infrastructure communication, and third-party service integration while requiring certificate management infrastructure and key lifecycle processes.

Network segmentation isolates safety-critical vehicle networks from entertainment, connectivity, and diagnostic systems that present larger attack surfaces. Security gateways control information flow between network domains, implement intrusion detection, and enforce security policies. However, segmentation complicates feature implementation requiring coordination across network boundaries and can create performance bottlenecks if implemented incorrectly.

Runtime monitoring detects anomalous behavior indicating potential security compromises, hardware failures, or software defects. Intrusion detection systems analyze network traffic, system calls, and operational patterns to identify suspicious activity. Security operations centers monitor fleet-wide security telemetry, coordinate incident response, and deploy countermeasures when threats are detected. This operational security infrastructure requires sustained investment, specialized personnel, and coordination with regulatory authorities when security incidents affect safety.

Update Management and Feature Deployment

Over-the-air update capability represents both a key benefit and significant operational challenge for software-defined vehicles. Organizations must establish secure update delivery mechanisms, validation processes ensuring updates don’t introduce safety hazards, rollback procedures for problematic deployments, and customer communication strategies addressing update notifications and forced update policies.

Update delivery employs either complete system image replacement requiring large data transfers and extended installation times or differential updates transmitting only changes for faster deployment and reduced data consumption. Organizations balance update granularity against system complexity, carefully managing dependencies between software components that must update atomically to maintain system integrity.

Validation before deployment employs staged rollout strategies that initially deploy updates to limited vehicle populations enabling monitoring for unexpected behavior before fleet-wide distribution. Canary deployments test updates in controlled environments approximating real-world conditions while limiting exposure if problems emerge. Automated testing suites validate updates against regression test cases, safety scenarios, and performance benchmarks before authorization for deployment.

Rollback capability enables reverting to previous software versions when updates cause unexpected behavior or safety concerns. Implementing rollback requires maintaining multiple software versions on vehicle storage, ensuring previous versions remain functional after newer versions execute, and establishing mechanisms to detect conditions requiring rollback activation. Some failures cannot be resolved through rollback, particularly if they involve persistent state corruption or hardware incompatibility, requiring additional recovery mechanisms.

Data Governance and Privacy Compliance

Software-defined vehicles generate substantial data volumes including location traces, driving patterns, vehicle performance metrics, environmental sensor readings, and usage information. Organizations must establish data governance frameworks addressing collection policies, privacy protection, retention periods, sharing restrictions, and compliance with evolving privacy regulations across different jurisdictions.

Data minimization principles limit collection to information required for legitimate purposes, reducing privacy exposure and storage costs. Purpose limitation restricts data usage to explicit purposes disclosed during collection, preventing unplanned secondary uses that could surprise customers or violate regulations. Consent management provides mechanisms for customers to authorize or restrict data collection and usage, requiring user interfaces for preference specification and backend systems enforcing customer choices.

Privacy regulations vary substantially across jurisdictions, with European General Data Protection Regulation establishing stringent requirements for data processing transparency, subject access rights, and deletion capabilities. California Consumer Privacy Act creates similar obligations for vehicles sold in California. China’s Personal Information Protection Law imposes localization requirements and restricts international data transfers. Organizations must implement technical controls enabling compliance with multiple regulatory frameworks simultaneously while managing cost and complexity of jurisdiction-specific implementations.

Frequently Asked Questions

How do software-defined vehicles differ from traditional vehicles with electronic control systems?

Traditional vehicles employ distributed electronic control units with fixed software loaded during manufacturing and rarely updated afterward. Each controller performs specific functions using software tightly coupled to hardware. Software-defined vehicles implement centralized or zonal computing architectures where software abstracts from hardware through middleware layers. Vehicle behavior is determined by software that can be updated remotely, adding new features and improving existing capabilities throughout the vehicle’s operational life. The fundamental distinction lies in software updateability, hardware abstraction, and continuous capability evolution rather than static configuration.

What prevents existing vehicles from being converted to software-defined architectures?

Converting traditional vehicles to software-defined architectures requires replacing electrical/electronic architecture, wiring harnesses, computing hardware, and communication networks—essentially complete vehicle redesign. Existing platforms lack sufficient computing power, appropriate network bandwidth, hardware abstraction capabilities, and secure update mechanisms. The physical architecture of traditional vehicles, with distributed control units integrated into mechanical assemblies, prevents retrofitting centralized computing without disassembling major vehicle systems. Economic and safety considerations make conversion impractical, requiring manufacturers to develop new vehicle platforms designed as software-defined systems from inception.

How do regulatory authorities ensure software-defined vehicles remain safe after over-the-air updates?

Regulatory approaches to software-defined vehicle safety evolve across jurisdictions. UNECE WP.29 Regulation 155 requires manufacturers to implement cybersecurity management systems demonstrating systematic processes for software validation, update authorization, and post-deployment monitoring. Manufacturers must establish software update management systems meeting requirements in UNECE R156, including documentation of update procedures, validation testing protocols, and traceability of deployed software versions. In the United States, NHTSA automotive programs develop measurement science and standards supporting automated vehicle technologies while maintaining voluntary guidance approaches rather than mandatory certification requirements. Ongoing regulatory development addresses gaps as experience with deployed software-defined vehicles accumulates.

What organizational capabilities do manufacturers need to successfully deploy software-defined vehicles?

Successful software-defined vehicle deployment requires software development capabilities including architecture design, embedded systems programming, cloud infrastructure management, and DevOps practices. Organizations need cybersecurity expertise encompassing threat modeling, secure development practices, and security operations. Validation capabilities must encompass simulation-based testing, formal verification methods, and over-the-air update management. Data analytics teams extract value from vehicle-generated information. Legal and regulatory specialists navigate evolving compliance requirements. Customer experience teams manage ongoing manufacturer-customer relationships extending beyond vehicle purchase. Most established manufacturers lack these capabilities internally and employ strategies combining internal development, technology partnerships, acquisitions, and contractor relationships to assemble required competencies.

How does software-defined vehicle architecture affect automotive supply chains?

Software-defined vehicles disrupt traditional tier-based supply chains where suppliers deliver discrete hardware components. Value creation shifts toward software capabilities, requiring suppliers to develop software engineering competencies, cloud infrastructure expertise, and system integration skills. Suppliers that successfully transition provide not just hardware but complete solutions including software, ongoing updates, and data services. This transformation favors suppliers with mature software organizations, potentially enabling new entrants from technology sectors while challenging traditional mechanical component suppliers. Contractual relationships evolve from one-time component delivery toward ongoing software licensing, service delivery, and revenue sharing arrangements. Supply chain security becomes critical as software vulnerabilities in supplier-provided components can affect entire vehicle fleets.

What business models do software-defined vehicles enable beyond traditional vehicle sales?

Software-defined architectures enable subscription-based feature activation where customers pay recurring fees for advanced driver assistance, connectivity services, or performance enhancements. Feature-on-demand models allow temporary capability purchase for specific use cases like additional range for long trips or enhanced performance for recreational driving. Usage-based services charge based on actual feature utilization rather than permanent entitlement. Data monetization creates revenue from aggregated vehicle information supporting urban planning, traffic management, or commercial services. Platform business models allow third-party developers to create applications running on vehicle computing platforms. These recurring revenue opportunities complement traditional vehicle sales, potentially representing substantial portions of total lifecycle revenue as markets mature and customer acceptance grows.

Key Takeaways

- Software-Defined Vehicles abstract vehicle functionality from fixed hardware through centralized computing architectures, service-oriented software designs, and over-the-air update mechanisms, enabling continuous capability evolution and feature deployment throughout operational lifecycles rather than static configurations determined at manufacturing.

- The transition from hardware-centric to software-defined vehicles represents fundamental industry transformation affecting competitive dynamics, organizational structures, talent requirements, and value capture mechanisms, with market projections indicating expansion from $470 billion in 2026 to $1.19 trillion by 2036.

- Implementation challenges include cybersecurity risks from concentrated computing infrastructure, software complexity exceeding 100 million lines of code, organizational transformation requirements from traditional automotive engineering toward software-centric development, and regulatory uncertainty for vehicles that gain capabilities post-production.

- Strategic implications extend beyond automotive manufacturing to affect transportation infrastructure planning, smart city development, mobility service models, and supply chain structures, as software capabilities become determining factors in vehicle differentiation, operational flexibility, and ecosystem participation opportunities.